JFK’s Cigars and the Embargo That Changed Everything

He filled his humidor, then changed cigar history forever.

Listen While You Read 🎧

Hit play and let the story unfold as you read — this one’s a blend of irony, ritual, and the quiet smoke of history.

A Thousand Petit Coronas and One Big Irony

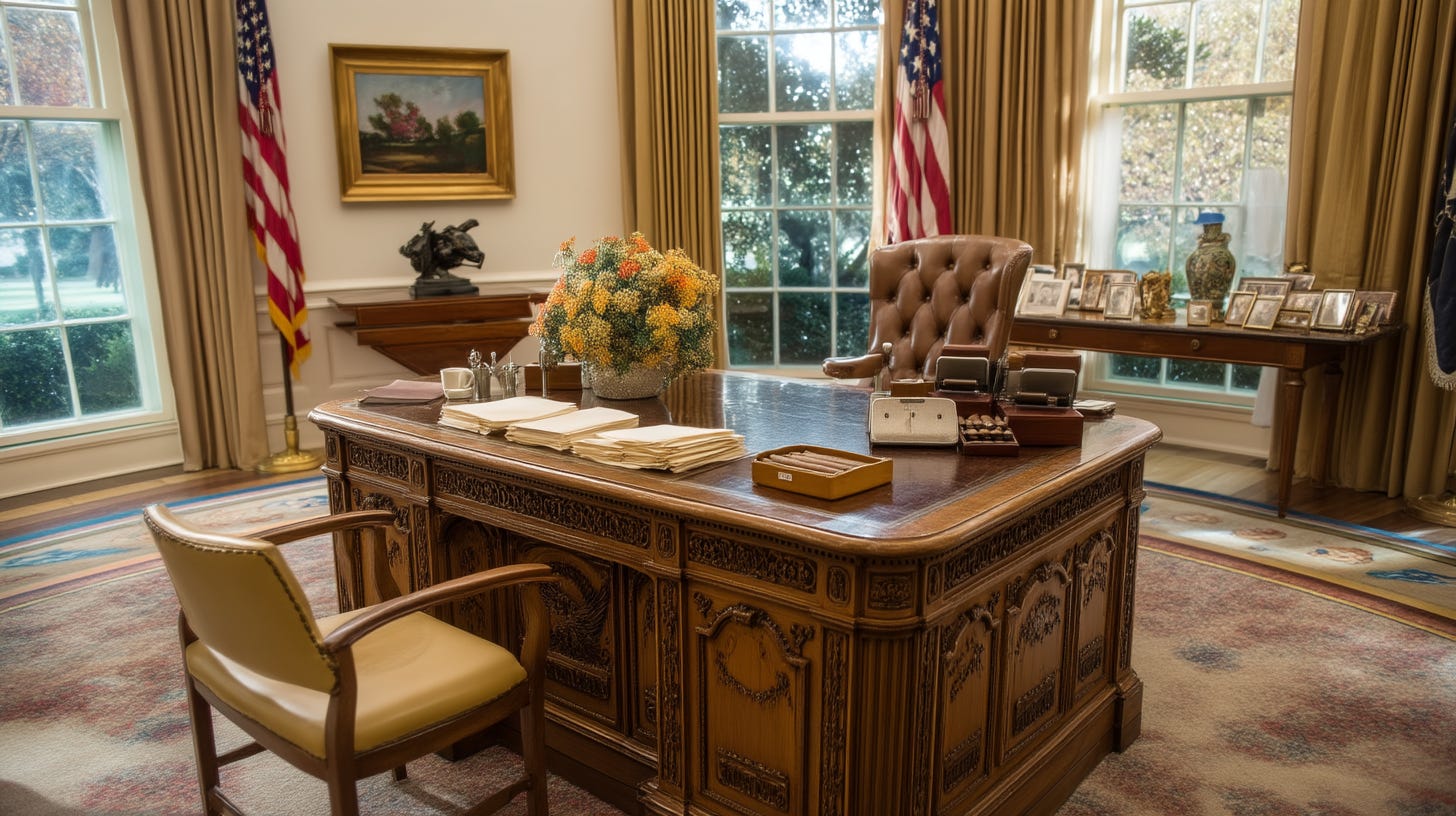

The Oval Office was quiet that night — the kind of stillness that only comes when the day’s decisions have already been made. A lamp glowed on the Resolute Desk, papers scattered, the faint scent of tobacco lingering in the air. Somewhere beyond those walls, the Cold War ticked like a slow fuse.

John F. Kennedy leaned back, exhaled, and gave a peculiar instruction to his press secretary, Pierre Salinger:

“Pierre,” he said, “I need you to get me a lot of cigars — very quickly.”

The number he had in mind? About a thousand.

Salinger, to his eternal credit, didn’t ask why. He just got to work — calling every tobacconist he knew, clearing out shop shelves across Washington D.C. By morning, he had gathered more than 1,200 of Kennedy’s favourite H. Upmann Petit Coronas.

When he returned, Kennedy smiled, reached into his desk, and signed the document that would make those cigars illegal for everyone else.

The year was 1962, and the document was Proclamation 3447 — the order launching the Cuban trade embargo.

Historians can argue the exact timing, but the image endures: a president quietly stocking his humidor before shutting the door on an island that once supplied America’s most beloved smokes. It’s almost too poetic. And maybe that’s why the story refuses to fade — not because of the politics, but because of what it reveals about ritual.

Every cigar lover has one. The way you clip the cap, toast the foot, and take that first patient draw. It’s not the nicotine — it’s the rhythm. The pause. The tiny act of defiance against a world that won’t stop moving.

For Kennedy, the Petit Corona was that pause. Compact, flavorful, refined. Not a Churchillian display of bravado — a quiet breath between crises.

But here’s the twist no one planned for: the embargo didn’t just make Cuban cigars “forbidden fruit.” It rewired the global cigar map.

Within a few years, exiled families and ambitious blenders were building new homes for old traditions. Santiago de los Caballeros in the Dominican Republic became a heartbeat of premium cigars — a place where consistency and elegance took center stage. Factories grew, farms spread across the Cibao Valley, and a new generation of rollers learned to perfect long-filler blends that didn’t try to imitate Cuba so much as answer it.

Farther west, Estelí, Nicaragua, went from a small town to a capital of strength and spice. The soils of Jalapa and Condega provided blenders with a bolder palette — earthy, peppery, and sometimes volcanic — and a freedom to experiment that reshaped modern profiles. Drive the Pan-American highway today and you’ll see the proof: bustling factories, drying barns, and rows of tobacco that wave like flags in the evening wind.

And then there’s Danlí, Honduras, with its own rustic charm — leaf that leans leathery and warm, blends that favor balance, and houses that married Cuban technique to Honduran character. Add in Ecuador for its cloud-grown wrappers — silky, elastic, and photogenic under studio lights — and you start to see the scale of what bloomed.

The embargo, meant to isolate, accidentally globalized. It scattered masters across borders, transplanted seed genetics, and created entire local economies where none existed. New jobs. New craft lineages. New flavor languages.

Even branding is split in two. Names like Romeo y Julieta, Montecristo, and Partagás came into existence in parallel — Cuban on the island, non-Cuban in the free world — each with loyalists convinced that theirs is the soul of the label. It was messy, sometimes litigious, but undeniably creative. The result? A richer, broader cigar culture than anyone in 1962 could have predicted.

There were also cultural ripple effects. A “ratings era” rose — glossy magazines, blind tastings, year-end lists. Cigar lounges spread through North America like neighbourhood living rooms: leather chairs, low conversation, a handshake culture that felt oddly timeless in a world sprinting toward screens. The American palate matured alongside this boom, discovering that “non-Cuban” wasn’t a compromise — it was a canvas.

And of course, the mystique only deepened. Tell people they can’t have something and watch how quickly it turns into legend. Cuban cigars became stories as much as objects — whispered comparisons, duty-free folklore, that one friend who swears he tried a Cohiba in Paris and it changed his life. Whether you buy into the myth or not, you can’t deny the power of a door marked “Do Not Enter.”

Meanwhile, the people who make this world possible — farmers, fermenters, torcedores — found livelihoods in new places. You can stand in a curing barn in Estelí and feel the hum of an industry that owes its existence to a signature in Washington, D.C. The irony is almost cinematic: an attempt to punish one island helped seed prosperity across several others.

Was that the plan? Of course not. It was an accident of history — the kind that keeps historians up at night and gives cigar lovers a conversation that never ends.

So yes, I like to picture Kennedy taking a Petit Corona from his freshly stocked stash, lighting it slowly, and savouring that first curl of smoke — knowing, or maybe not knowing, that he’d just changed the cigar world forever. He didn’t talk much about cigars in public, but his actions said plenty. Cigars were his steadying ritual in a life of turbulence, his private treaty with time.

And if there’s a lesson for the rest of us, it’s this: rituals matter. A good cigar doesn’t stop the world from spinning, but it gives you a way to meet it with a clear head and a calmer heartbeat. Out of all the unintended consequences of that February decision, maybe the most surprising is how it taught a whole new generation not just what to smoke — but why.

Cigar Lover’s Reflection:

We all have that one ritual — the small, steady comfort that keeps the day from swallowing us whole. For some, it’s a quiet drive. For others, a glass of bourbon at sunset. For Kennedy, it was a Petit Corona. For millions who came after, it became a world of Dominican elegance, Nicaraguan power, and Honduran warmth — an unlikely inheritance from a pen stroke meant to end something, and instead, to begin it.

What do you think — clever foresight, pure indulgence, or one of history’s significant “butterfly effects”? Drop your thoughts below 👇 I’d love to hear how you interpret this story.